Larry Beckett: there’s poetry in everything

Larry Beckett is an American poet and translator, among other creative pursuits. He wrote the lyrics to the well-known song “Song to the Siren,” made famous by Jeff Buckley and later covered by artists such as Sinéad O’Connor, Bryan Ferry, and This Mortal Coil. Yet Mr. Beckett is much more than a lyricist. His long-form poems, translations of Chinese poetry, and other works are equally important, and it was an honor to explore his creative process and the way he works.

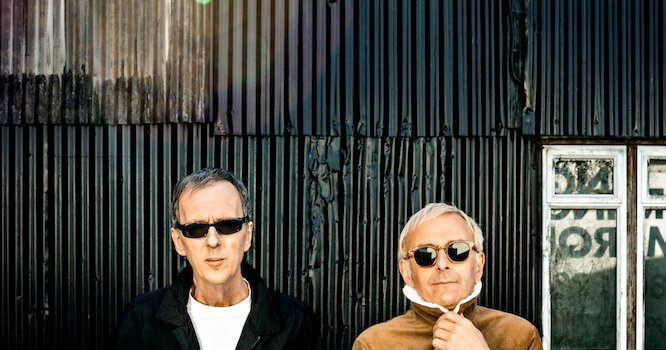

Larry Beckett

I really enjoyed reading your poetry and listening to the songs with your lyrics, so it’s an honor for me to be able to speak to you.

And actually, I’m very excited to be talking to you, because I love Franz Kafka. Last year, I read his uncensored diaries, and they’re all talking about old Prague, the Café Savoy, the Karlův Bridge, the castle, all that. It’s like I know it.

That’s great! I just read your book, Song to the Siren, and found it really beautiful to just read, and not analyze everything. I was thinking about this song, because there are so many cover versions, and you probably must have heard 50 of them. What is it like to hear your words sung by yet another person who chose them to cover?

Yeah, well, like an enduring piece of music, it can be played in different ways, and they’re all good. There’s not one definitive way, there could be many different ways to play, let’s say the Moonlight Sonata by Beethoven.You could play it at a different speed, or at different dynamics, and just like that, words that aspire to great art can be interpreted in different ways, and so that’s how I look at the different versions as I hear them. I don’t prefer one to another, but I enjoy the different slant that they have.

You also recorded a version, or several versions of it; it was that album from the 80s, also with other songs, and so the way that you recorded it was very different than, for example, Sinéad O’Connor’s. How did you like recording this album and the other stuff? I know that you are a musician also, obviously, and what is it like for you to work in a studio?

Well, the real story is that when I was starting out, I was not able to sing, in 1967. I was not able to play guitar, I was not able to play piano, and meanwhile I was surrounded by wonderful musicians who were being recorded by important record labels, things like that. So, I was completely intimidated, but I loved music passionately, so what I would do is I would wait until I was all alone, and then I would sing, and then I would try to play. And I did that every day for decades, and at the end I could sing on pitch, and I could play piano, and I could play guitar.

But I still I thought, well, I’m the poet, they’re the musicians. Then one day my wife listened to my latest work and said, you’re a musician. So I graduated. And actually, last year and this year, I’ve started to play concerts. And that’s really exciting for me.

The album, Last Session at Studio B, I think you’re talking about, from 1984. That was just a chance encounter. I didn’t go into studios, I didn’t share my music.

But my friend who was the engineer at the studio said, it’s Elvis Presley’s studio, and this is the last night. Tomorrow they’re selling everything, they’re dismantling the studio. Do you want to come? Couldn’t say no. I said, yeah, I’ve got songs. So we went in at two o’clock in the morning, and I played on Elvis Presley’s piano. And using his microphone and his studio to do it. That was just one in a million. And I actually have not recorded in a studio since then. Except my contribution to Eyelid’s album, The Accidental Falls, where I played the piano and harpsichord.

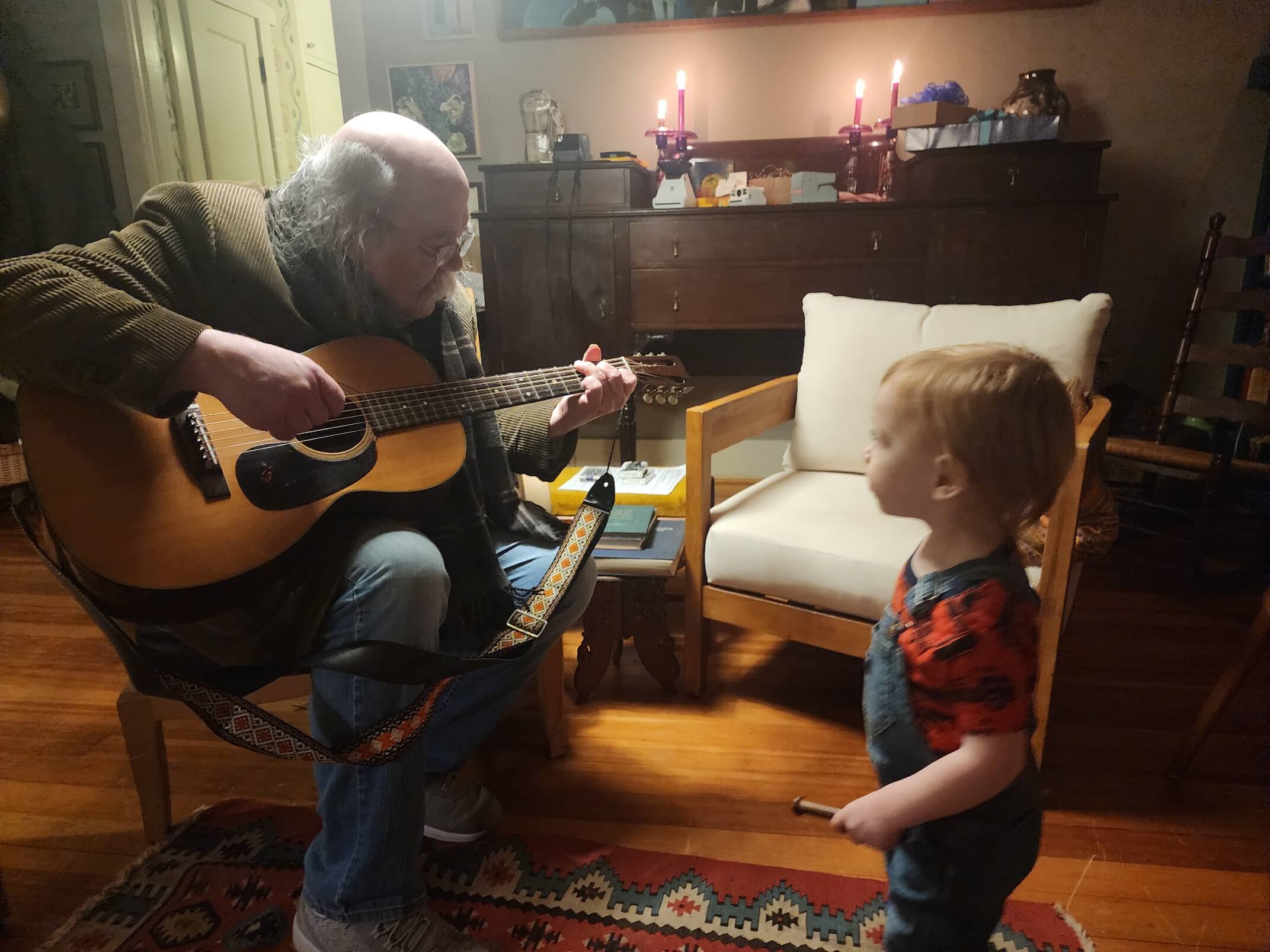

Larry Beckett playing guitar to his grandson

You didn’t start it off as somebody who writes, you wanted to be a physicist, right?

Yeah, and what happened was, my English teacher in high school took note of one of my compositions and thought that it deserved being shown. So he brought some important people from the school district in to hear me recite my piece. Afterwards, he asked me what my plans for life were. I said, I’m going to be a theoretical physicist. And he laughed. That was a shock. He laughed at me and said, no, you’re a writer. And then I went home and I thought about it, and I realized I’d been secretly writing poetry every day for years. And I knew nothing about theoretical physics. It was all a dream to be as smart as Einstein. Yeah, yeah, it’s true. And then I’ve kind of come full circle because one of my recent groups of poems is a sequence of poems, 26 poems called Holograph. And it’s inspired by the physics and the mathematics of quantum physics. So I did a lot of research. I had to learn quantum physics in order to write poetry that a quantum physicist would understand. In the notes in the back, I reference all of the physicists, and then I include the equations, too.

Do you think there are many similarities between language and mathematics or speech and natural science? Or is it something very different?

My vision is that there’s poetry in everything. Poetry doesn’t have to be about a beautiful flower in a beautiful meadow. It can be about the city, or it can be about a rocket to the moon, or it can be about anything. It can be about a good love affair or a bad one. That poetry is open and ready for anything.

And so there’s poetry in mathematics. The way, the certainty, and the kind of charisma of the gestures that are made in mathematical equations have a kind of poetry. And also the ideas of the physics behind them now. The math is simply stating something that the physics has discovered.

Has the way that you work changed much since the 60s when you were starting off?

It has really changed over the years. In general, it’s been hard work. I work on it all the time. And that hard work is broken up by times of inspiration where it’s easier, where I just naturally come upon good words. But for many years, it was extremely painful for me to write because I had a really high standard of beauty. I wanted each line to be beautiful. I would write these long pieces, you know, a book-length poem. And I would want every line to be radiantly beautiful. And if it wasn’t, then I would feel like it was a failure.

And then a strange thing happened. I was working on a long poem about Amelia Earhart. And I decided on a form inspired by old poems from Shakespeare’s day. And I wrote the whole poem in this meter, in this measure, in this form. I had to rearrange the words sometimes to make the half-rhymes work and so on. But at that point, for whatever reason, that formal necessity gave me pleasure. It gave me pleasure to write each line. And since then, it’s all been pleasant. I somehow banished the cycle of pain and replaced it with pleasure.

And do you remember what part of the poem was it when this happened?

It opens up with some blank verse, which is unrhymed. But as soon as it got into the half-rhyming part, that sense of pleasure started to blossom for me. I don’t really understand. And also, in recent years, inspiration has come to me more easily. I’ll be reading a book and then suddenly a whole song may come into my head, the whole song complete. And I just stop reading and pull out my notebook and write it down. I don’t know how that works, but I’m happy about it.

That’s beautiful. I mean, lots of musicians say that they don’t know where the songs come from. So it makes sense that it’s mysterious for you.

Plato thinks that there’s a special place where these rules of mathematics and objects of beauty live, and that human beings in certain states of mind access that place. I used to think that was crazy, but now I think Plato might be right.

You wrote so many works that were very long, like 100 pages long. How do you know when it’s finished?

When I started writing these book-length poems, that was very unfashionable. I was completely ignoring what was going on in poetry and just following my own desire.

In a short poem, I think you can know when it’s done. Yeats talked about finding the last perfect word in the poem, closing like a box with a snap. And I’ve felt that many times where I work on a short poem, and I know from having done it before when it’s ready, when it’s done.

But a long poem, it’s kind of shaggy, there’s all these loose edges and things, and it’s hard to know. But in general, I have a plan of what all the different sections of the poem are going to be. And I try to do each one until I’m happy with it. And that could be a long time, years. Usually, what I do is about two years for these long poems, like two or so years of research. Because I really want the piece to be authentic and true to the subject. And so I do research, some studying what scholars have done, and some of my own research, too. And then another couple of years of writing, until I’m happy that each section does what it was supposed to do.

I write really slowly, maybe only a few lines a day, but it adds up.

Do you work every day?

I study poetry every day, but I don’t write it every day.

You also translated a lot of things.

I have translated lots, and actually I have a project with a publisher in Chicago to publish nine books this year of my translations. From Chinese, from Greek, from German, and from French. One of them is going to be published also by University Press. That’s my Verlaine book.

How did you learn Chinese?

There was a revolution in poetic translation around 1960. Before that, let’s say poems by Li Po, the Chinese poet, would be translated by a Chinese scholar who understood all the characters of ancient Chinese, and who would then write out a literal translation. The problem there is that they lost all of the poetry. There’s no music, there’s no sensuality, there’s no compression. They just have these long, baggy lines full of explanation. And you would read that, you would get an idea for what the original poem must have been. But you don’t get any pleasure at all. You don’t get the poetry. There is no poetry. So that was a problem.

And then an American poet, Robert Lowell, made a book called Imitations. He wouldn’t say translations, he was too shy to say that, because actually he was translating from languages he didn’t know, like Russian. Like he translated poems by Pasternak. He would get a prose version, a literal prose version, use that and create a new poem in English that was patterned after the old poem in Russian. So now he’s translating or imitating the original, and what he ends up with is a powerful poem. And you read this and go, now I see why people love Pasternak in Russian.

And he did that with Montale in Italian and Rimbaud in French and so on, all through this book. That set an example and now I use the same method. I learned a little bit of Chinese and I learned about the old forms that their poetry took. Then I read the scholarly translations and try to do in English what the original poem did in Chinese. Initially it was just because I felt a kinship with Li Po, but I also then did a volume of poems by Li Shang-yin, in the Tang Dynasty, kind of the love poet of ancient China. And then I worked on the Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu and did a book called The Way of Rain. So those are my Chinese translations.

And then there’s more and more. Every Friday I work on translations.

And how about Goethe? How about German?

I try to translate poems that haven’t been translated. So with Goethe, it’s the West–Östlicher Divan, a very long book that was inspired by the Middle Eastern poetry of Hafiz. In Germany, the most beloved book of his besides Faust is this and here it was completely unknown because there were no good translations.

So I worked for a number of years on it, and I not only translated it, but I tried to keep the original rhythms and rhymes so that you really feel like you’re reading the Goethe book. But if there was a great translation of it out there. I wouldn’t have even started.

The Verlaine book is actually two books that I’ve translated, Romances Without Words, that’s very famous, Romances Sans Paroles, maybe the most loved book of lyric poetry in France. And he wrote it while running around with his friend, the poet Arthur Rimbaud. And then the next thing that happened is that they became lovers and then they quarreled and Verlaine tried to shoot Rimbaud, went to prison for two years in solitary confinement. So he was in a cell by himself and they let him have paper and pen. So he wrote a book of poetry in those two years. Some of the best poetry he had ever written was in prison. And then when he got out, he gave the poetry manuscript to a publisher and the publisher said, you’re crazy. You’re a disgrace. You’re a felon. You’re a criminal. You don’t want to advertise this fact by putting out your book that you wrote in solitary confinement. So forget it.

So what he did was he went on living and publishing and writing. And then when he would put out a new book of poetry, he’d take a few of the prison poems and put them in it, sometimes rewritten and actually not improved. So then all these years go by and everyone publishes and translates the original books of Verlaine, but nobody touches the prison manuscript. I found a copy in French of the manuscript. And that was in about 2005, it came out. And then I decided that I would be the first person to translate the original complete prison manuscript of Verlaine. And that’s the book In Solitary.

I noticed that you mentioned Italy and Venice in your poems, Italy and Venice. Do you have some kind of special relationship to Italy?

I’ve been there two times, northern Italy, and I do especially love to be there. And I think of modern poetry as coming from the lyric poetry of Dante that’s inspired by the Troubadours. And also the Divine Comedy, of course.

And then also to, for me and lots of other people, the greatest lyric poet who ever lived is a man named Eugenio Montale. A Nobel Prize laureate in 1975. And before then he was not very well known, but he wrote three books that are the most beautiful, powerful lyric poems ever written. He’s a perfect poet in that his poems aren’t too old fashioned, but they are not too new. They’re right in the middle, there’s an edge about them. And they’re not too beautiful, but they’re not too ugly.

So between Dante and Montale, it’shard not to be engaged with the Italian spirit, but maybe you’re noticing something that I haven’t noticed.

You have quite a lot of plans.

There are books and also maybe some readings. And when I do these concerts, I always recite some poems as well. Long poems. I don’t think like everybody else. So to me, publishing a poem means reading it out loud to people.

So even though there’s this big book, American Cycle, all of the long poems in it, actually you can find on the internet me reading the whole thing. Sometimes it takes three hours, but that doesn’t matter. I still go ahead and do it.

Maybe it’s the old style. Maybe that’s what they were doing before they were printing books of full of poetry. I think it was the way to share.

It’s the old way. And I mean, that’s how Homer worked. He would recite. And that’s how Shakespeare worked. He wrote his plays to be spoken on stage. And the oral part of poetry is most important to me. And so I’ve recorded all of the long poems complete.

Is there anything else you want to mention before we finish?

I’m working on publishing a book of sonnets that I wrote over a period of 50 years. Almost like one a year. That is maybe the best writing I’ve done, but it’s still unpublished. These days, I’m trying to resurrect the ode based on models by Pindar and Dante. And so that’s what I’m writing today.

Larry Beckett

Website of Larry Beckett:

https://www.larrybeckettpoet.com/

Current book:

Other books by Larry Beckett:

Additional book links:

From the American Cycle

https://www.amazon.com/

U. S. Rivers: Highway 1

https://www.amazon.com/dp/

U. S. Rivers: Route 66

https://www.amazon.com/dp/

Read also:

Jeffrey Martin, the gigapixel guy: There is a good sense of personal freedom in Prague

Photos: Biennale di Venezia 2024