Interview: Martin Salajka

Trafo Gallery presents the exhibition Nebula by painter Martin Salajka (*1981), drawing on his long-term and intense relationship with nature. In his paintings, the artist captures a personal experience of the landscape as a space of constant movement, transformation, and tension between life and decay. The exhibition features works pulsating with the energy of natural elements, mist, water depths, and dark forests, where reality merges with visions and hallucinatory imagery. The exhibition opens on 8 January 2026 at 7 pm. A guided tour will take place on 4 February at 6 pm, followed by a children’s workshop on 14 February from 2 pm to 5 pm. A bilingual publication designed by Martin Pecina will accompany the exhibition. More information is available at www.trafogallery.cz

In his current exhibition, Martin Salajka returns to the place he has never truly left. It is as if the testimony of nature—where everything began—has now become more urgent than ever. The painter confronts us with what he has personally lived through, which in the very specific environment of his studio materialises into a multitude of paintings. He moves among them as if engaged in some wild dance or ritual. Although nature in these works is full of unsettling phenomena, it is precisely being in nature that grants the painter the only measure of calm he can find.

“From the chaos of the world, which hurts more and more, I’ve spent much of this year escaping into nature with my sketchbook and my dog to listen to the silence—falling asleep while looking at the sky, waking to mists, watching the sun draw with light into the billows of vapour and seeing everything reflected on the water’s surface. I looked beneath that surface into darkness and marshy decay, felt the vibrations—the dance of tubifex worms in the sludge, the fierce energy of fish, water currents, the rising from the bottom toward the light and back again, the dance of trees and winds. The movement and vibration of life and death. Each day and night by the water multiplies the intensity of the previous ones. The images return from the chaos, take shape in sketches, and now it is time to inscribe them onto the canvases. To tame the chaos I can grasp, and to hope I can do it—and that someone will understand,” Martin Salajka says about his work.

His permanent restlessness, his inability to concentrate or work systematically, seems to resonate with the instability of the contemporary world. A certain inner raggedness also characterises his work, which constantly hovers on the boundary between the real and the unreal, the abstract and the concrete. Within a single canvas, several painterly registers may alternate—from glowing, impasto layers to finer, more drawing-like strokes. The paintings pulse with the fast, aggressive, as well as the slow and heavy rhythms of metal music, which is an integral part of the creative process and often uncompromisingly guides the painter’s hand.

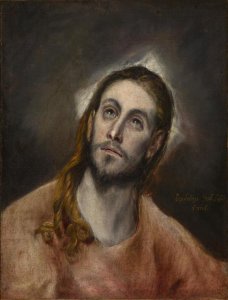

A crucial, though not physically present, role is also played by the human in canvases inspired by Salajka’s journey to Congo, undertaken with fellow artists in autumn 2024. Fiery demons, water spirits, or storm clouds appear as personified natural forces unleashed by human insensitivity and arrogance in interfering with ecosystems. The mystery and symbolic woundedness of nature is thus accompanied by its dangerously enigmatic aspect—one that threatens the blind human with the terrifying forces of its revenge.

Still lifes, a permanent component of Salajka’s work, remain present as well. Alongside flowers referencing the eternal theme of vanitas, extinguished, smouldering candles now appear. It is precisely the motif of smoke and vapour that links these works to the exhibition’s overarching theme. Nebula—meaning clouds or vapours—can, in a broader sense, signify anything unclear, blurred, or changing. These are the mists drifting above the pond’s surface, the murky waters, the wind-swirled dust, the vapours rising from the nostrils of nocturnal creatures. At first indistinct, the forms within the paintings gradually sharpen in the viewer’s eye; the imagination tirelessly works, new forms emerge from the depths, silence transforms into an infinite multiplicity of sounds, and from mere stains arise the hidden spirits of nature. What was once immaterial becomes transferred into reality.

Trafo Gallery,

Hala 14, Pražská tržnice, Bubenské nábřeží 306/13, Praha 7, tram 1, 12, 14, 25, metro Vltavská (300 m), open Tue–Sun 15–19 h, Sat 10–19 h, www.trafogallery.cz, IG: trafo_gallery

INTERVIEW

KJ: Martin, your last exhibition at Trafo Gallery was five years ago. Has there been any fundamental shift in your work since then?

MS: I feel that certain lines of my work have been developing throughout my entire life. At the beginning of everything there is my interest in nature and growing up in it—touching the principles I carry within me and understand intuitively. The main motif in the current exhibition is a return to the primal things that shaped me: being in nature, fishing, perceiving the landscape and the processes unfolding in it. On top of that come other influences, such as the trip to Congo in September 2024, which introduced far greater expressivity into my painting because of the rawness and wildness of the local nature. The paintings I made after Congo were created very quickly, gesturally, and this added new elements to my painterly language.

KJ: I also sense that recently you’ve moved away from the urban landscape, which played an important role in your previous exhibition.

MS: It was quite logical at the time that I depicted the city too, because during those years I wasn’t visiting nature much. The pace of exhibition life and navigating interpersonal relationships kept me more in Prague. Last year I returned to nature more often, partly because I have a new dog, and this reignited my passion for fishing along with a desire to distance myself from people a bit. Congo also became a source of thoughts concerning human rapaciousness toward nature, so I suppose I need a little break from people.

KJ: What was it like going on a trip with a group of artists?

MS: For me, challenging, because by nature I’m a loner. The art world is a complicated environment, competitive, and although I get along with many of those people, it was difficult for me to be constantly in their presence and dealing with topics from the art world. Very often I simply don’t want to listen to such issues. Most of my friends come from other fields; interestingly, my closest circle consists entirely of psychotherapists. I tend to talk with people whose interests lie elsewhere than in the art world discourse. Sometimes it all feels incredibly distracting and unsettling.

KJ: Do current social issues make their way into your art, or do you avoid them entirely?

MS: One doesn’t live in a vacuum of course. I follow politics, though lately it has horrified me—similar to the art world, which is also political in its own way. I’m appalled by how much power and money seem to dominate everything, something I understood even more in Congo. Africa is still colonised, perhaps today by China, but it’s all interconnected. China wouldn’t need to acquire resources if it weren’t producing things for the Western world. We can pretend colonialism is our dark past, but given how interconnected the world is and how it struggles to satisfy Western consumption, we remain part of the problem. The world is a complicated place right now. I don’t need to name these issues analytically or explicitly in my work—I can approach them metaphorically. When I saw those fires in Congo, for instance, I painted the forces unleashed from destroyed ecosystems, taking shape as demons that will torment us.

KJ: Are these demons, i.e. the dark forces we release through our insensitive destruction of nature, a new theme that you brought back from Congo, or had something similar appeared in your work before?

MS: I think it’s a theme that has permeated my work all along. Anyone who fishes can see that rivers lack water, that riparian forests are drying out, that something is going wrong. I don’t depict these issues literally, but I notice the gradual disappearance of nature, its fragility, the cycle of life, recycling, transformation… a negative transformation now because of the influence of humans. I feel it and express it, though not scientifically; more through intuition and metaphor. There’s also a certain acceptance: life’s energy is endlessly recycled, there have already been several mass extinctions, let’s prepare for another.

KJ: You often talk about fishing, something you have done since childhood. What does the silence by the water mean to you?

MS: Lately, fishing isn’t just about catching fish. It’s about calming down, sitting in one place, observing what happens in the landscape, experiencing emotions connected to fear or discomfort, or pure joy from witnessing natural phenomena. Being there alone with my dog, communicating without words. David Lynch wrote a book, Catching the Big Fish, where he speaks in metaphors and says, for example: “Ideas are like fish. If you want to catch little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you’ve got to go deeper.” One realises that hunting is an archetypal activity, a place to think about one’s life—what constitutes success, what one longs for. Do you want lots of small fish or one big one? Do you want to kill and eat the fish, or simply meet it, outwit it, and release it? I go there to rest, to think about what’s happening under the water, to experience a struggle with my own comfort, with the weather, with the fish. It connects me to something fundamentally human that we are losing, namely, our ability to work with instinct and intuition. To quieten down to the extent that one stops thinking in ordinary contours and rejoices simply at the miracle of a swan flying overhead. Encounters with animals are deeply fascinating to me. And over the last twenty years I’ve spent more time with dogs than with people. The human world makes less and less sense to me, even though I am, of course, part of it.

KJ: How much time by the water do you need to feel your mind calm down?

MS: Ideally at least three days, so there’s at least one full day when you don’t have to deal with anything.

KJ: Why does mountainous landscape never appear in your paintings? Is it because of the environment you grew up in?

MS: I’ve wondered about that too. I think it’s partly because painting mountains in a convincing way is difficult. But it’s also because of where I was born and raised. The Lower Morava Valley is completely flat, and I’ve always liked watery, swampy, changeable environments—that’s where I move most naturally.

KJ: A dog has been your companion for many years. Currently it’s Alf, a Staffordshire Bull Terrier. What does a dog mean to you as a being?

MS: A dog is an absolutely pure creature, acting spontaneously. Every day he can make me laugh or lift my mood. Communicating without words is wonderful, and it gives me a sense of calm. In nature dogs notice completely different things than humans. They’re our guides—beautiful, pure souls I understand well. With Alf I also enjoy his strength, his toothy mouth, his energy. It’s another connection to nature, even while the dog is also somewhat foreign to it. I often dream about dogs—dogs I’ve had—they speak to me, I talk with them. Recently I dreamed that I was walking with my dog and we met another dog who joined us. I kept looking for his owner and he said: “No, no—you’re my owner. I’m the dog you will have in the future.” And he told me that my future would be good—“like a marrow bone.”

KJ: And what does the dog symbolise in your paintings?

MS: Often dogs serve as guides for humans—they see more. My first dog led me home countless times when I was drunk. My second dog hated it when I was drunk, so I stopped drinking partly because of him. Paradoxically, dogs humanised me the most. I enjoy Alf also because of his rough, raw energy, which resonates strongly with my own.

KJ: A love of dogs is also something you share with one of your major artistic influences, Josef Váchal, who surrounded himself with them his whole life. What else do you feel you and Váchal have in common?

MS: In Váchal’s work I find countless precisely observed elements from nature. And in his cycle Šumava Dying and Romantic, you can sense that he perceived ecological issues far ahead of his time. I also found in him the key to not being ashamed of my vision, not being afraid of being something of an oddball.

KJ: You paint to music, mostly heavier music, especially metal. Is it the music that gives your paintings their rhythm?

MS: Heavy music is extremely important to me. Metal is full of exaggeration, but also melody and solid structures, but all within a certain expressiveness that is completely natural to me—I don’t have to force it. I like expressiveness with detail; in metal you have riffs that echo the fast strokes on the canvas, and then a little solo that allows me to paint something more detailed.

KJ: Your paintings can be perceived neither as records of reality nor as abstraction. How should we look at them?

MS: In some sense, they contain both—it’s a kind of abstracted reality, or more like a hallucination or dream of reality. What interests me is finding some kind of artistic shortcut. I don’t want to grope my way around the world or search for the exact shades of leaves on a tree. I’m more interested in what’s happening on that tree, what might have happened, what the tree might have seen, what it grows from. I perceive the world and nature as cycles. In this sense, altered states of consciousness are absolutely relevant in art.

KJ: This also relates closely to the title of the exhibition. Nebula means fog or cloud, but also something mysterious, indistinct, i.e. nebulous. Why did you choose this title?

MS: Because this sort of fog, smoke, sludge, as well as the sky connected to everything happening below, fit the paintings perfectly; that’s exactly what’s happening in them. Nebula is also a cannabis strain, which for me is a legitimate part of the creative process. Observing paintings or sketching in a slightly altered state of consciousness helps me concentrate, something I generally struggle with because of diagnosed ADHD.

KJ: Looking at your creative process, which is strongly based on layering, can you describe it in more detail?

MS: My work is very chaotic, not systematic at all. Usually I stretch a huge number of canvases and spend months preparing the grounds. On fishing trips I make sketches and at the same time I begin building the painting through stains. The paintings remain abstract for a long time, and then I start inserting a motif and connecting it with the background. Then come the narratives themselves, along with more and more layers. Painting is the communication of layers and strokes.

KJ: And what is that final stroke?

MS: The most complex one. You have to muster up the courage to make the final statement, which can completely change the meaning of the entire work. As with a book or a film, the ending is crucial; it can ruin everything or leave it shrouded in mystery.

KJ: I think layering for you isn’t just a matter of material or technique. What is it connected to in terms of content?

MS: Every environment has many layers, many spatial planes that relate to each other, and something can happen in each of them. What fascinates me about painting is how the brushwork of painters I admire flows like natural elements. The principles of clean, design-like paintings are foreign to me. Things rooted in pop art or street art, with their forms and colours, feel like synthetic matter, and understandably appeal more to people who grew up in cities, playing with Lego bricks, while I was moulding things out of mud. The core motif of my childhood was to get outside into nature.

KJ: Do you choose colours intuitively or do you plan them more in advance?

MS: I like working in two modes: one muted and melancholic, the other almost aggressively colourful. For me, colour is mainly a carrier of emotion. I enjoy bright colours—I’m not looking for perfect harmony, I use colour the way aggressive guitar sounds function in music. Lately I’ve been listening to psychedelic, atmospheric music as well, so then I work with more subdued tones.

KJ: You also work more with large formats than with small canvases.

MS: Large formats are closer to me because you can physically enter them. The force of the stroke contains a physical movement. But small formats can help me calm down a bit.

KJ: You’ve been engaged with various printmaking techniques for a long time. Do you have a current favourite?

MS: Lately I’ve been working mostly with lithography, but I also have a press in the studio. I’ve always enjoyed aquatint, etching and linocut. I like connecting printmaking with painting. For example, I’ve printed linocuts on canvas and then painted over them, or I’ve inserted a print into the painting to introduce an element of fine drawing, which I then continue to develop and draw into.

KJ: You chose your old pal Martin Pecina as graphic designer for the exhibition and the catalogue. How long have you known each other, and what does your relationship mean to you?

MS: Martin and I have known each other since I was 15. We spent a lot of time together in high school, mostly at various parties, and we share a mutual understanding. We got up to all kinds of mischief. I respect him deeply as someone who started out in ordinary advertising studios but one day decided he wanted to design books and went on to build a strong reputation in the field. He does everything thoroughly. A huge part of my life is tied to Martin.